Civil Wrongs is a series of investigations into historic injustices and the impact they have today. This radio version is adapted from a two-part podcast produced by WKNO and the Institute for Public Service Reporting. See below for links to the podcasts.

Every day, for 26 years, Carla Peacher-Ryan wore a gold ring on her finger—a big, four-karat diamond, passed down from her step-grandmother.

"What I had heard was this ring was probably her engagement ring," she says, "and that she may have been married to a mayor of a small town."

That town is Earle, Arkansas, about 30 miles west of Memphis. The heirloom, she learned, was connected to an infamous crime. A friend had read about it in a book.

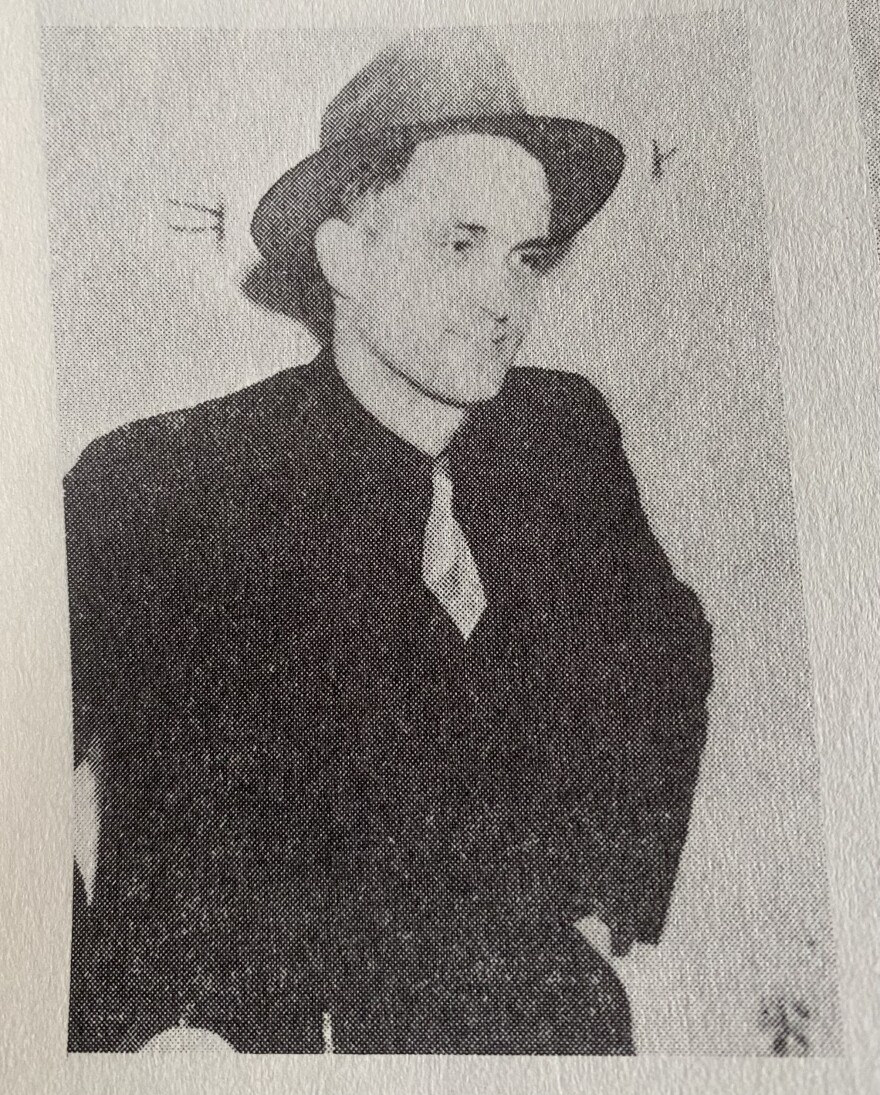

Carla shared a surname with the perpetrator. The friend asked if she’d heard of a Paul Peacher, who had been a sheriff’s deputy.

In 1936, the federal government indicted him for holding people as slaves.

A visit to ancestry.com confirmed the man was her grandfather’s brother. For Carla, a retired lawyer heavily involved with social justice organizations, the family connection stung.

"There's nothing that would have taken the shock away," she says.

So what brought these slavery charges to rural Arkansas 70 years after its abolition? That part’s less shocking.

The 13th Amendment makes an exception for people convicted of crimes; they can be forced to work.

And for deputy Paul Peacher, that loophole presented an opportunity.

"He was a terror. He was a terror for the Black people of the town," said John Twist in a 1993 interview from the Henry Hampton Collection at Washington University Library.

Twist was the grandson of a plantation owner near Earle in the 1930s.

"He just demanded immediate obedience," Twist said.

In an irony not lost on students of history, Peacher’s scheme arose from a need for cheap labor to clear land for farming. The Great Depression had caused cotton prices to drop. Wealthy landowners in eastern Arkansas needed low-wage workers.

“March of Time,”a popular newsreel series seen in movie theaters before the main feature, described the crisis this way: "In all the United States, there is no parallel to the economic bondage in which cotton holds the South."

While landowners were receiving federal subsidies, there was no trickle down to the people actually working the land: tenant farmers and sharecroppers. Many were earning what would be $18 a day in today’s money, and falling deeper in debt to their landlords.

In 1934, a small group of workers formed the Southern Tenant Farmers Union to strike for better wages. In a bold move that captured national attention, Black and white members joined forces. It meant that landowners couldn’t play the races against each other. But they would still try.

"That's where Paul Peacher and these other people came in," says Michael K. Honey, a labor and civil rights historian.

Black workers, he says, were particularly vulnerable to intimidation. "All hell came down on them."

Sheriff’s deputy Paul Peacher knew that if Black workers feared the law more than they feared breaking a strike, he could undermine union efforts.

The officer quickly rounded up eight men on charges of vagrancy—essentially being jobless. The local judge, who was also the mayor of Earle, fined each of them the equivalent of $560 today.

Since they didn’t have the cash, they’d have to pay in hard labor. The judge handed them right back over to the man who had arrested them.

Today, the population of Earle is just under 2,000, about the same size it was in the 1930s. Just off the highway, two-lane state roads turn into the gravel roads that lead to vast acres of cropland.

On a recent visit to this area, Marquette Smith thought about his own family connection. He learned through researchers at the University of Memphis's Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change that his great uncle had been one of Peacher's prisoners.

"I just imagine what it looked like, you know, during that time in the 1930s," he says.

They were brought to this tract of land Peacher was leasing from the school district. Nothing survives of the three small structures that housed the men, built with iron bars over the windows.

"They were strong men to go though that," Smith says.

But the plan backfired after a white preacher from Memphis secretly visited the prisoners and learned the truth. By sheer coincidence, he had a college connection to the Attorney General of the United States. Federal investigators soon descended on Earle. The scandal made national headlines and forced Arkansas’s governor to release the men.

The feds weren’t finished. Paul Peacher was soon indicted under a rarely used anti-slavery law.

At his federal trial, Peacher was confident his all-white jury would find him innocent. But jurors punted, declining to issue a verdict.

Federal Judge John Martineau wouldn’t have it. "Every circumstance points to the guilt of this man,” he told them. “This is not a lone case in Arkansas. It ought to be stopped."

On a second attempt, Peacher was found guilty.

For Arkansas lawyer Robert Thompson who has studied the case, both the prosecution and the outcome were remarkable for the time.

"In 1936, that's probably the best measure of justice that you could expect," Thompson says.

Peacher’s sentence? Two years probation and a fine of about $79,000 in today’s money. He also lost his job.

"Sunlight is the best disinfectant. You know, if you shine a light on something that nobody wants to see, you sort of force change," Thompson says.

For Carla Peacher-Ryan, the law’s targeting of poor Black workers to support the interests white people was an all too-common thread in American history.

"The whole thing just reminds me so clearly of the game that's been played since the founding of this country," Peacher-Ryan says.

Then there was her diamond ring. Through research by the Hooks Institute, she learned her step-grandmother was related to the Earle, Arkansas mayor and judge who had sentenced the men to work for Peacher.

"The ring had become a symbol of racial terror and social injustice. So I thought: what if it could have a new role addressing those issues?"

She auctioned the ring and gave the money—$15,000—to the Institute.

Michael K. Honey says that while the incident highlighted a flaw in the constitution, it also showed the power of organized labor when workers set aside racial differences.

"That gave people hope that it might be possible to have a movement, where you could get across these racial boundaries and build some unity among poor people and working class people," he says.

In the years that followed, the Civil Rights Movement would remember the lessons learned in Arkansas.

Racial unity became a driving principle of Martin Luther King Jr.s’ Poor People’s Campaign, and even now, as income disparity widens. If one group can be forced to work for less money, all workers can suffer.

The exploitations of slavery still echo today and we should not fail to recognize the sound.

Audio in this story is used with permission from Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive, the Henry Hampton Collection at Washington University Libraries, and the West Virginia Press and the family of John Handcox for the songs “Raggedy, Raggedy Are We” and "Mean Things Happening in this Land." Additional music is by Andrew J. Crutcher.

LISTEN TO THE CIVIL WRONGS PODCASTS OF SEASON 3: "NOTHIN' FOR OUR LABOR"

Part 1: The Sheriff and the Sharecroppers

Description: In the middle of a strike by a rare interracial labor union in the 1930s, a sheriff’s deputy in Earle, Arkansas named Paul Peacher falsely arrested more than a dozen Black men for vagrancy and got them sentenced to work on land he was leasing. In this episode, you’ll meet Peacher’s great-niece and relatives of two of the Black men that Peacher enslaved. You’ll also hear the story behind the labor union that helped push for basic workers’ rights we have today.

Part 2: Treatment or Punishment

Description: Lawsuits nationwide threaten unpaid labor in exchange for substance abuse treatment. Program participants are suing work therapy programs for being treated like an unpaid workforce. Centers say they are beneficiaries, not employees. But does work in and of itself help treat substance use disorders? We talk to experts, break down the legal background and arguments, and talk to two people who have been through work therapy programs in Memphis.

Copyright 2024 WKNO. To see more, visit WKNO. 9(MDA4MDYxNjY4MDEzMTQ2OTkxMzkyOWU2NQ004))